Introduction:Legends of vampires have stalked the human imagination for centuries, casting long shadows from Old World villages to modern American towns. There’s something irresistibly spooky about the vampire myth – the idea of the undead rising from graves to drink blood, a concept deeply rooted in folkloric legends and supernatural beings. How have these eerie tales persisted, and what truth (if any) lurks behind the legends? In this investigative feature, we sink our teeth into the history of vampire folklore, tracing its ancient roots and following its bloody trail into the United States. With a journalistic eye and a spooky tone, we’ll explore how historical vampire myths influenced real beliefs in America, and how pop culture – from Dracula to Buffy the Vampire Slayer – continually resurrects these nocturnal creatures in our imaginations. Prepare for a journey through graveyards and old libraries, where tales of pale skin, red eyes, and nocturnal predators blur the line between myth and reality.

Ancient Origins of Vampire Folklore

Vampire folklore is far older than the United States. To truly understand how Americans came to fear the undead, we must begin where the myths began – in the Old World. Ancient beliefs about blood-drinking demons and restless spirits span many cultures. In Ancient Greece, for example, there were legends of vampiric monsters like Lamia and Empusa. These creatures preyed on the living under cover of night, much like later vampires. Ancient Greek mythology didn’t use the word vampire, but it described evil spirits and demons with vampire-like traits. According to recent research, the Greeks told of a monster named Lamia – once a queen cursed by the gods – who became a child-eating demon that drank human blood. Another Greek fiend, Empusa, was said to shape shift into a beautiful woman to seduce men and then devour them, an ancient precursor to the seductress vampires of modern fiction. These earlyvampire folklorefigures show that the fear ofblood-hungry creatures is truly ancient.

Meanwhile, across Eastern Europe, peasants for centuries whispered about vampire–like entities roaming the night. Long before the word vampire entered the English language, Slavic and Balkan cultures dreaded the upir or vrykolakas – essentially, revenants who rose from the grave to torment the living. In medieval Eastern Europe, the line between evil spirits and corporeal vampires was blurry. People believed that certain dead individuals might return as vampires, especially if they had been wicked in life or if no proper funeral rites were performed. They would visit loved ones after death, caused mischief, and spread death and disease. In some cultures, decapitation was a common method to ensure the vampire’s head was separated from the body, preventing the vampire from rising again. The word “vampire” itself has origins in these Eastern European languages. It first appeared in English around the early 1700s after Austria encountered vampire “epidemics” in Serbia. In fact, Austrian officials reported cases of “suspected vampires” causing panic in villages, and these reports introduced the word vampire (then spelled vampyre) to Western Europe. Thus, through news pamphlets and travelers’ tales, the Old World vampire myths traveled to colonial America, setting the stage for a new chapter of vampire myth in the New World.

Vampires Cross the Ocean: Folklore in Early America

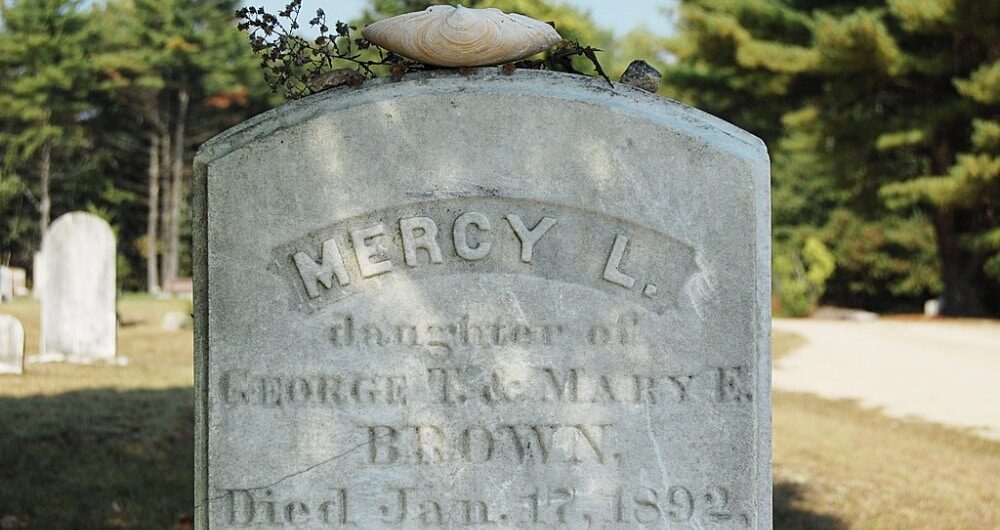

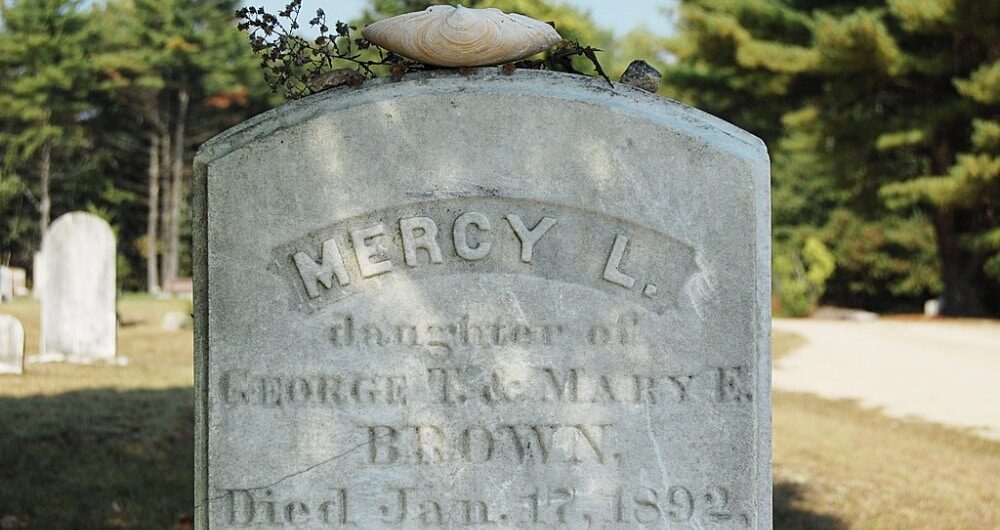

How did vampire lore find its way to the United States? The process was gradual and fueled by immigration and literature. European colonists and later immigrants brought their vampire folklore with them. In the 18th and 19th centuries, as New Englanders heard whispers of Old World vampire cases, a few communities began to interpret mysterious deaths through the lens of the vampire myth. By the 1800s, rural parts of New England were gripped by what historians now call the New England Vampire Panic – a real-life fear that the dead were preying on the living. Such fiction, originating in 18th-century poetry and 19th-century short stories, played a significant role in shaping the vampire lore that took root in America. One of the most famous cases was that of Mercy Brown of Rhode Island. In 1892, Mercy Brown died of a wasting illness (tuberculosis), and soon her brother fell ill with the same symptoms.

Distraught and desperate, Mercy’s family and neighbors grew convinced that Mercy might be an undead corpse draining the life from her sibling. In a scene straight out of a horror tale, they exhumed her body from the cemetery in Exeter. The corpse was oddly well-preserved, which, to their 19th-century minds, was proof that Mercy was a vampire. According to reports, Mercy’s heart was removed and burned – a grisly attempt to stop the undead attack. This macabre incident, known as the Mercy Brown vampire incident, is one of America’s best-documented pieces of vampire folklore. It shows how European vampire myths took root in U.S. soil: frightened communities, faced with unexplained deaths, resorted to old folk beliefs. Mercy was not alone. Historian Michael Bell documented about 80 similar “vampire” exhumations in New England, with many corpses staked or tampered with to prevent them rising. These weren’t vampires in the Hollywood sense, but panicked villagers truly believed they were dealing with the undead.

Interestingly, many of these incidents coincided with outbreaks of tuberculosis (the “wasting disease” once called consumption). In hindsight, the symptoms – pale skin, sunken eyes, coughing blood – made frightened observers suspect a vampire was spiritually draining blood from the victims. In an era before germ theory, blaming an undead creature was a way to make sense of the senseless. Folklorists note that people believed performing rituals (like burning the heart or reburying the body with a stake through the chest) would stop the vampire’s mischief.

These practices were the other methods communities used when faced with a mysterious plague, and they were decidedlyrealto those involved. The fact that Americans in the 1800s engaged in vampire hunting– digging up bodies of suspected vampires– shows the powerful hold of the vampire myth. The New England vampire scares predate Dracula and Hollywood, yet they read like living folklore: the old world undeadlegend transplanted into Yankee farmland. (It’s even said that news clippings of the Mercy Brown case reached Bram Stoker as he was writingDracula, possibly inspiring aspects of his novel.) Thus, vampire folklore became part of American history well before pop culture cemented it in our minds.

The 1892 gravestone of Mercy L. Brown in Exeter, Rhode Island. Mercy’s exhumation during the New England vampire panic illustrates how vampire folklore influenced real beliefs in the U.S.

From Dracula to Twilight Saga: Vampires in Popular Culture

No discussion of vampires is complete without Dracula – the most famous vampire of all. Bram Stoker’s 1897 novel Dracula was a gothic masterpiece that firmly defined the modern image of the vampire: an aristocratic Transylvanian count with pale skin, a cape, and a thirst for human blood. Stoker drew on earlier vampire folklore and fiction (such as Lord Ruthven, the suave vampire character in John Polidori’s 1819 story The Vampyre). But it wasDracula that became the blueprint for vampires in pop culture. The novel’s immense success sank its fangs into the Western imagination and hasn’t let go since. Early 20th-century films likeNosferatu (1922) brought Dracula’s menace to the screen – Count Orlok inNosferatuappears as a cadaverous, rat-toothed monster, arguably closer to the ghastly undead of folklore than Stoker’s refined Count. Universal’s Dracula(1931) introduced the world to Bela Lugosi’s iconic portrayal: the slicked-back hair, hypnotic stare, and thick accent, defining the vampire aesthetic for decades. These works turned thevampire mythinto a pop-culture staple.

Fast-forward to the late 20th century and vampires were enjoying yet another renaissance – or perhaps un-deadresurrection – in American media. In 1967, Barnabas Collins, a brooding vampire character, debuted on the gothic television soap Dark Shadows, bringing vampire drama into American living rooms every afternoon. The 1970s and 1980s gave us the Vampire Chronicles of Anne Rice, beginning with Interview with the Vampire (1976). Rice’s novels, featuring the elegant vampire Lestat, explored the psychology and eternal angst of vampires, painting them as sympathetic anti-heroes dripping with charisma and blood. This trend of humanizing vampires continued into the 1990s with Buffy the Vampire Slayer. The 1997–2003 TV series (and its spin-off Angel) cleverly blended horror, humor, and teen drama in a California setting. Buffy showed vampires as dangerous creatures of the night – Buffy famously slays them with wooden stakes – yet it also gave us soulful vampire characters like Angel and Spike who struggled with their undeadnature. The show’s witty, pop-culture-laced dialogue and strong heroine gained a cult following, further cementing vampires in the zeitgeist. By the late 2000s, the Twilight Saga had catapulted vampires into an entirely new level of mainstream fame. Stephenie Meyer’s Twilight novels (and the blockbuster films) reimagined vampires as romantic heroes in a supernatural teen love story. Edward Cullen, the vampire protagonist of Twilight, has pale skin, glittering in the sunlight (rather than burning – a controversial twist on vampire lore), and he refrains from drinking human blood, opting for animal blood instead. Twilight toned down the horror in favor of star-crossed romance, attracting a massive young audience and sparking debates among fans about what “counts” as a vampire. Love it or hate it, Twilight proved that the vampire myth could evolve with the times and still enthrall millions.

Not to be outdone, television kept the blood flowing. HBO’s True Blood (2008–2014), based on Charlaine Harris’s novels, presented a modern Southern Gothic take – imagine vampires “coming out” to society and coexisting (uneasily) with humans, sustained by a synthetic bottled blood called “True Blood.” The show oozed sex, violence, and social commentary, with fanged characters integrating (and often clashing) with normal society. Around the same time, The Vampire Diaries on CW offered a teen drama spin with love triangles and ancient vampire lore in small-town America. From Dracula stage plays a century ago to today’s TV and streaming hits, vampires have proven endlessly adaptable. They serve as mirrors to our fears and desires – sometimes literally in stories where they mind control victims or seduce with unearthly charm. Pop culture has taken the old folklore of monstrous revenants and given us vampires as tragic anti-heroes, suave villains, reluctant saviors, or even high school heartthrobs. And yet, whether in a horror novel or a romance movie, certain core elements of the vampire folklore remain recognizable: immortality, blood-drinking, and the curse of the undead.

A stylized illustration of Count Dracula looming over a dark castle. From Stoker’s Dracula to the Twilight Saga, vampires have evolved but remain rooted in the same vampire folklore traditions.

Identifying and Hunting Suspected Vampires

How can you tell if that odd neighbor or reclusive count might be a vampire? Over the years, folklore and fiction have offered plenty of clues for identifying vampires – as well as ways to defeat them. Classic vampire folklore describes a host of telltale traits and behaviors that set vampires apart from a normal human. Below are some of the most common signs of a vampire, drawn from traditions around the world:

Pale Skin and Altered Appearance: Vampires are often said to have deathly pale skin (as they are corpses or avoid sunlight). In some tales they have a gaunt or corpse-like visage, while in others they appear as an unnervingly beautiful version of their former self. Red eyes are sometimes mentioned, especially right after feeding on bloodwhen their thirst is sated. In other cases, a vampire might have no reflection in mirrors or cast no shadow, marking them as an unnatural undead being.

Blood Drinking and Fangs: Almost all vampire legends involve the creature drinking blood. This is their primary sustenance – the blood of the living gives them life and unnatural strength. Many cultures imagine vampires with sharp teeth or fangs to facilitate this grisly diet (though interestingly, the original Eastern European folklore did not always include fangs – that detail became popular later). Victims drained of human blood and left pale were a suspicious sign. If corpses were dug up and found with fresh blood on their mouth, villagers took it as proof of vampirism.

Restless Undead Nature: Vampires are dead persons animated by dark forces, hence the term undead. They might be found in their graves looking unnaturally preserved (since they aren’t truly alive or decaying normally). In folklore, when suspected vampires were exhumed, witnesses claimed the body looked “fresh” or had blood in the heart, leading to panicked accusations. The idea that a dead person could claw out of the grave to harass the living was at the heart of vampire scares.

Unique Abilities: Vampires often have powers beyond those of any normal human. Superhuman strength and agility are givens. Many tales grant them mind control or hypnotic influence over victims – the ability to bend a person’s will, making the victim invite the vampire in or forget the encounter. Shape-shifting is another unique ability: in Eastern European lore and popular fiction alike, vampires can shape shift into animals. Bats are the classic form (inspired by real vampire bats, which added a zoological twist to the myth), but also wolves, rats, or mist. In Bram Stoker’s Dracula, the Count famously takes the form of a bat or wolf at will. This shape shiftingability makes the vampire a particularly elusive foe. Additionally, some stories give vampires the power of flight or the ability to climb walls like a lizard – all adding to their eerie repertoire.

Aversion to Sunlight and Holy Symbols: “Children of the night” prefer darkness. In many myths, sunlight weakens or outright destroys vampires (though notably, this wasn’t universal in early folklore – it was popularized by movies like Nosferatu). Still, the pale, nocturnal vampire is now standard. They are creatures of the evening, often sleeping in coffins by day. Holy items are also commonly said to repel them: a crucifix, a Bible, or consecrated objects like holy water can burn or injure a vampire. The idea likely stems from vampires being seen as blasphemous or demonic. Holy water, when sprinkled on a vampire, is thought to sizzle and scar their flesh as if it were acid. Garlic, while not holy, is another famous repellent – an old folk remedy in Europe was to hang garlic cloves to keep vampires (and other evil spirits) away with its pungent odor.

Armed with the above knowledge, how did people historically hunt or defend against vampires? Folklore offers other methods to neutralize the threat of the undead. A wooden stake through the heart is the most iconic method – a literal way to pin the vampire’s corpse to the earth. This was done in many a real exhumation of “suspected vampires,” as New England records attest and as Stoker immortalized in Dracula. Beheading the vampire (removing the vampire’s head) was another sure way to kill it in Slavic traditions – bury the head separate from the body to prevent reanimation. Burning the body to ashes was the final, albeit drastic, solution (and indeed Mercy Brown’s heart was burned). In fiction, silver bullets or objects sometimes work (an overlap with werewolf lore), and running water is said to bar or burn vampires (hence why Dracula must be carried over a stream). A vampire hunter of old would pack a kit filled with wooden stakes, mallets, garlic, vials of holy water, maybe a crucifix, and hope for the best. These kits, real or assembled after the fact, can be seen in museums – eerie testaments to how seriously our ancestors took the vampire threat.

It’s worth noting that not all vampires in folklore followed the exact same rules. Every culture and storyteller adds a twist – some vampires can enter homes uninvited, others cannot; some cast reflections, others do not. But the overarching image is consistent: a creature that looks human but isn’t, that sustains itself by draining life (usually via blood), and that is fundamentally undead – a dead body animated by a curse or evil force. Combine those traits with our very real fear of death and the dark, and it’s no wonder the vampire myth has such enduring power.

A close-up of a real vampire bat (Desmodus rotundus). Despite their name and diet of blood, vampire bats are small creatures that rarely bite humans. The discovery of these bats in the New World added a new dimension to vampire folklore, linking myths to nature.

Modern Vampires and Urban Legends

Even in an age of science and technology, the vampire continues to thrive in urban legends and fringe beliefs. Across many cultures, there are still whispers of blood-sucking entities and modern-day vampires—though these stories often take new forms. In some communities, people claim to be real vampires (usually meaning they consume small amounts of blood or energy from willing donors). These individuals form subcultures, complete with vampire clubs and modern daycovens, treating vampirism as an identity or lifestyle rather than a supernatural curse. While they don’t have the powers of fictional vampires, their existence shows how the vampire myth adapts even to modern times.

Around the world, local folklore still produces its own vampire-like creatures. In Latin America, for example, the legend of El Chupacabra (literally “goat-sucker”) emerged in the late 20th century – a creature said to drain livestock blood. Some call it a cryptid or urban legend, but it echoes the age-old fear of something stealthily drinking the blood of the living at night. In Africa, one finds tales of beings like the Asanbosam of Ghana (a vampiric figure with iron teeth) or in South Asia the figure of the Vetala or Bhūta (spirits that might possess corpses and feed on the living). Even the word“vampire”itself gets applied in unexpected ways – for instance, in energy healer circles, people talk about “psychic vampires” or individuals who “drain your energy” (a metaphorical use of vampire lore in modern life). Across many cultures, the concept of an entity that preys on others persist, whether literally or metaphorically.

Urban legends in the United States have occasionally featured vampires as well. In the 1970s, London had the Highgate Vampire hysteria, and around the same era in the U.S., some people in the San Francisco Bay Area whispered about a so-called vampire roaming the cemeteries (likely inspired by media). While these cases were mostly media-fueled frenzies rather than true folk belief, they show how the undead remain compelling. In the Internet age, fictional stories about vampires can easily spark “real” scares. A few years ago, a bizarre rumor spread online about a “vampire cult” in Texas, blurring the lines between cosplay and crime in the public eye. Though largely unfounded, the panic it incited was very similar to earlier vampire panics – demonstrating again that the old fears still lurk in our collective psyche.

Folklorists point out that modern times have transformed the vampire from a source of terror into a pop culture darling, but that doesn’t mean the underlying belief has vanished. To this day, there are occasional reports (often tabloid) of people conducting real vampirehuntsor staking corpses in remote parts of the world. For instance, in the early 2000s, panic over supposed vampire attacks led to mob violence in Malawi and later in Zambia – locals truly believed blood-sucking criminals or vampires were at work, and several people were accused or even killed due to the hysteria. These tragic episodes sound like echoes of the New England vampire panic, occurring in the 21st century. They remind us that vampire folklore is not just quaint history; in some places, it is living belief.

Even in the U.S., where we scientifically know vampires are fiction, the myth’s influence pops up in unique ways. Consider the enduring fascination with alleged vampire graves and haunting sites. Tourists leave plastic fangs and notes at Mercy Brown’s grave to this day. New Orleans – a city steeped in spooky lore – has vampire-themed tours and claims of “sightings” (helped along by Anne Rice’s literary legacy set in Louisiana). Some self-described vampires in New Orleans host vampire chronicles events, gathering to share experiences. None of these individuals claim to be the evil undead of legend, of course, but they embrace the mythos as a subculture. The fact that the vampire archetype can spawn everything from dangerous mobs to cosplay meetups underscores its flexibility and power.

AI-generated image of Abchanchu, a vampire figure from Bolivian folklore. Legends say Abchanchu appears as an elderly wanderer to lure victims. Such global vampire myths show the universality of the vampire folklore, adapting to different cultures and eras.

Finally, modern medicine has even offered retrospective explanations for vampire lore. Diseases like porphyria (a rare disorder affecting skin and blood) have been hypothesized to inspire vampire legends – sufferers might avoid sunlight due to skin sensitivity and have reddish teeth or crave raw flesh, giving a scientific basis for traits like avoiding sunlight and blood-drinking. While the porphyria-vampire link is more speculative than factual (and largely discredited by experts), it’s fascinating that science seeks to demystify ancient beliefs in vampires. Similarly, rabies has been suggested as an origin for some vampire traits – rabies can cause biting, aversion to light or water, and delirium, which loosely parallel vampire behavior. These theories remind us that behind many vampire myths might have been a kernel of misunderstood truth.

Conclusion:

From the crumbling castles of Transylvania to the quiet graveyards of New England, vampire myths have proven as hard to kill as their undead protagonists. The United States, though a relatively young nation, became fertile ground for these old tales – whether through actual vampire panics in the 1800s or through the explosion of vampire characters in our books, movies, and TV. There is a persistent mystery and allure to the figure of the vampire that keeps us looking over our shoulder on dark nights. Perhaps it’s the way vampires encapsulate so many fundamental human fears: death, the unknown, even the danger that a beloved family member might not rest peacefully. Or perhaps it’s the temptation of immortality and power that makes us, paradoxically, invite vampires into our imaginations again and again.

In the end, the vampire folklore in the U.S. is a rich tapestry woven from global threads – Eastern Europe legends, ancient Greece monsters, and homegrown New England superstitions – and embroidered by each generation’s storytellers. We may not truly fear vampires in our modern cities, but we love to tell their stories, to dress up as them on Halloween, and to binge-watch them in our favorite shows. The legend continues to evolve in contemporary urban legends and subcultures, proving that while the vampire itself may be undead, the idea of the vampire is truly immortal. As one folklorist aptly noted, vampires have transformed “from a source of fear to a source of entertainment”, yet in our collective psyche they remain lurking, forever ready to rise from the grave when the lights go out. The next time you hear a bump in the night or see a shadow flit by your window, you might smile and recall it’s just a vampire myth… or is it? In the realm of vampire folklore, the line between myth and reality can be as thin as a coffin lid. And that enduring uncertainty is exactly what keeps these undead creatures alive in our culture.

References & Sources: External research and historical accounts were used in this article. Notable sources include scholarly analyses of vampire folklore and documented cases like the Mercy Brown incident, as well as cultural retrospectives on vampires (e.g., GreekReporter on ancient Greek vampire-like legends, and Smithsonian Magazine’s coverage of New England vampire exhumations). These works provide factual context to the enduring mystery and vampire myths discussed here.